But it isn’t only that Jeeves’s judgment about clothes is infallible, though, of course, that’s really the main thing. The woman knows everything. There was the matter of that tip on the ‘Lincolnshire.’ I forget now how I got it, but it had the aspect of being the real, red-hot tabasco.

‘Jeeves,’ I said, for I’m fond of the woman, and like to do her a good turn when I can, ‘if you want to make a bit of money have something on Wonderchild for the ‘Lincolnshire.’‘

She shook her head.

‘I’d rather not, miss.’

‘But it’s the straight goods. I’m going to put my shirt on her.’

‘I do not recommend it, miss. The animal is not intended to win. Second place is what the stable is after.’

Perfect piffle, I thought, of course. How the deuce could Jeeves know anything about it? Still, you know what happened. Wonderchild led till she was breathing on the wire, and then Banana Fritter came along and nosed her out. I went straight home and rang for Jeeves.

‘After this,’ I said, ‘not another step for me without your advice. From now on consider yourself the brains of the establishment.’

‘Very good, miss. I shall endeavour to give satisfaction.’

As detailed elsewhere, I have been making something of a hobby of taking out-of-copyright classics and mildly desecrating them by swapping all the genders round. Not just the main characters, but everyone in the story down to every ‘Oh God’ becoming ‘Oh Goddess’. It’s a simplistic, binary change. It’s not a rewrite; it doesn’t introduce any new writing into the mix, unlike such mashups as (the surprisingly good) Pride and Prejudice and Zombies. But it does have the effect of creating – not exactly an alternative history, but an alternative literary past. Where women get to own property and men get to do sewing.

After I self-published Prejudice and Pride last year, I decided my next endeavour would be James Eyre. However, partway through editing it, I started thinking of other books that would be just as interesting to switch, and before long I realised that my next project was going to have to be a collection.

I ended up with a dozen writers ranging from the early 19th to the early 20th century; a chapter or two from each, and I found I had an anthology which gives the sense of an entire alternative literary canon. I ordered them by publication date, with Austen the oldest and Edith Wharton the newest. Here’s a bit from Sensibility and Sense, just after young impetuous Matthew Dashwood has had a fall:

A lady carrying a gun, with two pointers playing round her, was passing up the hill and within a few yards of Matthew, when his accident happened. She put down her gun and ran to his assistance. He had raised himself from the ground, but his foot had been twisted in his fall, and he was scarcely able to stand. The lady offered her services; and perceiving that his modesty declined what his situation rendered necessary, took him up in her arms without farther delay, and carried him down the hill.

And here, a century later, from The Age of Innocence:

He made no answer. His lips trembled into a smile, but the eyes remained distant and serious, as if bent on some ineffable vision. ‘Dear,’ Nuala whispered, pressing him to her: it was borne in on her that the first hours of being engaged, even if spent in a ball-room, had in them something grave and sacramental. What a new life it was going to be, with this whiteness, radiance, goodness at one’s side!

Virginal boys, chivalrous women and buffonish ladies-about-town advised by their wise ladies’ maid (or gentlewoman’s gentlewoman?) – and we haven’t even touched on The Wonderful Witch of Oz, June the Obscure or The Picture of Daria Gray, which is perhaps my favourite of all.

So if your curiosity is piqued, James Eyre and Other Genderswitched Stories is available in paperback for about £5.99 or on Kindle for about £1.50 depending where you are – links below. If neither works for you and you’d like a .pdf, email me on fausterella at gmail and we can sort something out. In the meantime, have a freebie chapter: Chapter 1 of The Picture of Daria Gray.

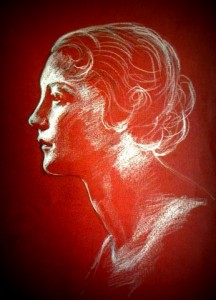

And finally, thanks to my father, artist John Harrad, for providing one of his drawings for the cover art, and to James Wallis for providing advice on formatting (though any mistakes remain my own. Or can be blamed on my toddler for climbing on the keyboard at the wrong moment).

I am honoured to have been allowed to lend a tiny hand in helping you get this delightful book out.

Hee, just spotted a “my dear fellow” in Portrait–it is rather untranslatable!

Someone pointed me to this on Twitter. It’s a fascinating idea, but I’m wondering what you do when you run up against actual biology — heroines getting pregnant, for instance, or characters whose fathers are too elderly to be their biological mothers. Does Lord (formerly Lady) Macbeth still say “I have given suck”?

It seems to me that assuming an alternative biology in which men are impregnated by women and breastfeed their children would mean you weren’t saying anything meaningful about actual men and women, just changing the words you use to refer to them. But to avoid that you’d have to go a lot further and tinker with plot as well as text. Would be interesting to know your thoughts…